Barbara Manning "Charm of Yesterday… Convenience of Tomorrow"

“Her best work outshines those of her bigger-selling peers. Manning’s artistic restlessness and her tendency to jump in and out of bands and recording situations makes it difficult to follow her career — her discography must be one of the most confusing in all of the ’90s indie scene — but it also makes her one of the most vital and interesting singer/songwriters of her era.” – Stewart Mason, All Music Guide

Maybe everything has been going to such shit lately because Barbara Manning has been hibernating. A Matador Records mainstay and pivotal indie-rock pioneer of the nineties, Manning has continually written material that matches the quality of the many songs she covers. Both as a performer and a listener, Barbara Manning is a passionate lifer. While her music is compact and succinct, it is steeped in multitudes of genre periods and styles. From SF Seals to her work with Stuart Moxham (Young Marble Giants) to The Go-Luckys, every collaboration carries her genius melodies and lyricism. In a four minute catchy song, Manning can communicate what others require novels to express. Her fans include Yo La Tengo, The Clean, Sonic Youth, Tall Dwarfs, Pavement, Calexico, The Replacements, and even Faust (don’t forget her prolific work as half of free-sound stalwarts Glands of External Secretion.)

With an upcoming tour joining Codeine, Manning felt the time was right for something new. Thus, Charm of Yesterday…Convenience of Tomorrow. It compiles a few different periods. Chico Daze is a song cycle that absorbed the dark times and experiences she had in Northern California through the 2010s. The Porch Series cover songs were Manning’s antidote to pandemic madness, and features the music by Elliott Smith, Edgar Winter, Richard & Linda Thompson, Galaxie 500, Bob Dylan and The Handsome Family.

Now situated near Los Angeles, where she works as a drama teacher, Manning has been playing live again and recording, channeling her innate sense of theatricality and dynamics into this new musical era. Charm of Yesterday…Convenience of Tomorrow heralds a new phase of releases for an iconic, legendary artist set to reintroduce herself and show how beautiful songwriting flames eternal.

Vince Clarke "Songs of Silence"

As the album title suggests, Songs of Silence is a lyricless, instrumental album, and is hugely evocative for that. Unlike anything you’ve previously heard from Vince Clarke as an artisan of dynamic electropop, Songs of Silence has about it a more sober ambient electronic beauty, its unique characteristics put it in a category of its own.

For the creation of the record Vince set himself two rules – first that the sounds he himself generated for the album would come solely from Eurorack (a modular synthesizer format introduced in the mid-90s) and secondly that each track would be based around one note, maintaining a single key throughout. The resultant pieces, with the Eurorack sound clay then manipulated on Logic Pro, amount to wordless narratives, in which a sense of synthgenerated, cosmic remoteness is often jolted by stark interventions, reminders of the human hand at work amid this machinery.

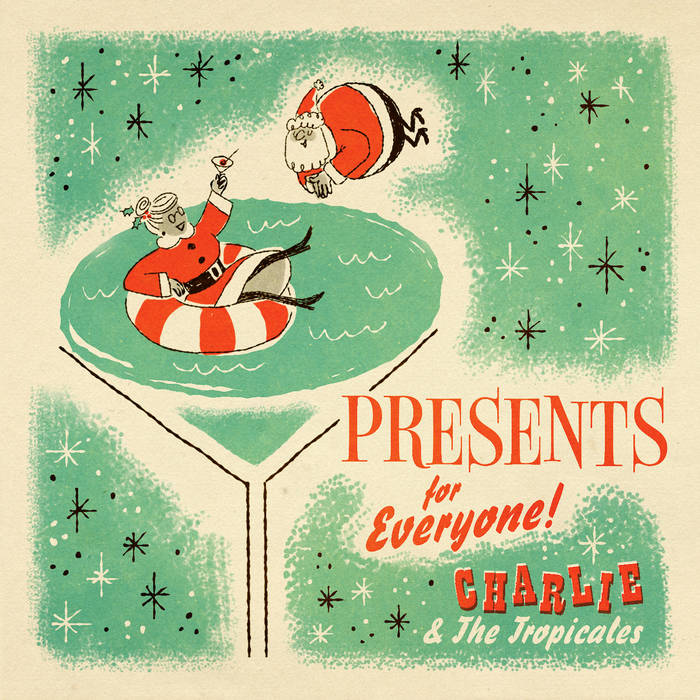

Charlie and the Tropicales "Presents for Everyone!"

Charlie & The Tropicales return with “Presents for Everyone!” – a collection of tropical holiday music by way of sunny New Orleans, the northern most port of the Caribbean! Go ahead and mix up a punch and throw a log on the fire, or open up the windows and dance around the tree – be it a douglass fir, coconut palm or Evergleam!

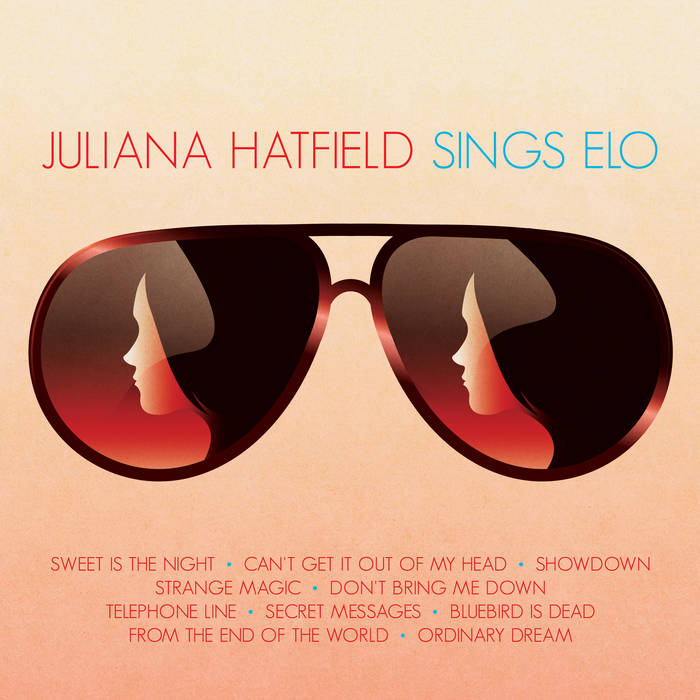

Juliana Hatfield "Sings ELO"

ELO songs were always coming on the radio when I was growing up. They were a reliable source of pleasure and fascination (except for “Fire On High” which scared the heck out of me). With this album of covers I wanted to get my hands deep into some of the massive ‘70’s hits but I am also shining a light on some of the later work (“Ordinary Dream” from 2001’s “Zoom” album, “Secret Messages” and “’From The End Of The World”, both from the ‘80’s).

Thematically, I identify with the loneliness and alienation and the outerspace-iness in the songs I chose. (I have always felt like I am part alien, not fully belonging to or in this Earth world.) Sonically, ELO recordings are like an amusement park packed with fun musical games with layers and layers of varied, meticulous parts for your ears to explore; production curiosities; huge, gorgeous stacks of awe-inspiring vocal harmony puzzles. My task was to try and break all the things down and reconstruct them subtly until they felt like mine.

Overall, I stuck pretty close to the originals’ structures while figuring out new ways to express or reference the unique and beloved ELO string arrangements. An orchestra would have been difficult or impossible for me to manage to record, nor did I think there was any point in trying to copy those parts as they originally were. Why not try to reimagine them within my zone of limitations? In some cases, I transposed string parts onto guitars, or keyboards, and I even sung some of them (as in “Showdown” and “Bluebird Is Dead”).

Recording the album was a kind of complicated and drawn-out process since I was doing all of my tracks at home in my bedroom (drums and bass were done by Chris Anzalone and Ed Valauskas, respectively [in their own recording spaces]), and I kept running into technology problems that would frustrate me and slow me up. But eventually I got it all done. A labor of love. -Juliana